On Tesla’s AI Day (September 30th, 2022), the company unveiled its first humanoid robot, offering a glimpse into the future of AI-powered robotics. Leveraging advanced perception techniques from its self-driving architecture, Tesla has integrated this technology into its robotics.

Prior to Tesla’s breakthrough, Boston Dynamics captivated the world with its remarkably human-like humanoid robots, featuring impressively smooth motions akin to human actions. Distinct from Tesla, most robots of that time relied on model-based control methods.

More recently, researchers have increasingly adopted learning-based control methods. Notably, Tesla has emphasized perception-based control, leveraging its advancements in autonomous driving technology.

Robotics is undergoing a significant transformation, with a quiet yet continuous shift from traditional control to learning-based control. The recent strides in Large Language Models (LLMs) have led the way in new opportunities and advancements in robotics.

AI technology has found widespread application in robotics, presenting itself in various forms. For example, AI can facilitate robots in executing complex tasks at the decision-making and planning levels. Furthermore, deep learning and data-driven AI techniques can enhance robots’ perceptual capabilities, making them more powerful.

Furthermore, AI-powered robots are increasingly employed in industrial settings and becoming more accessible to consumers. These AI-powered robots are capable of performing intricate tasks and interacting with humans more naturally.

Key Components

The foundations of AI in robotics cover a range of key ideas and methods that enable robots to demonstrate intelligent behavior. These foundations comprise perception, planning, and control. Moreover, learning and adaptation, and human-robot interaction are what we focused on from an AI perspective.

Perception equips robots with the ability to gather information about their environment while planning and control algorithms determine the optimal actions to achieve specific objectives. Control systems turn abstract commands into physical actions, and learning mechanisms enable robots to enhance their performance over time. Human-robot interaction emphasizes effective communication and collaboration. Altogether, these foundations form the groundwork for creating AI-powered robots capable of perceiving, reasoning, planning, and interacting with the world.

Perception

The perception system includes understanding the environment and self-location. This information is essential for robots to carry out planning and control tasks. Similar to humans, robots perceive the world using sensors and interact with it through vision, hearing, touch, and other sensory capabilities. Various methods of perception exist, and it’s crucial to gather information through different hardware devices.

- IMU(Inertial Measurement Unit): measures a body’s motion, for example, velocity, angular rate, acceleration, and sometimes the orientation of the body. It offers real-time information about the robot and is generally robust even in challenging environments. However, it suffers from integration drift over time, leading to inaccuracies in long-term measurements. Additionally, it cannot provide absolute information such as the position in a world-aligned coordinate system. A specific task where an IMU is crucial is in stabilizing robots.

- LiDAR sensor: precisely perceives the distance and shape of objects. However, it is costly, has a limited perception range, and is sensitive to ambient light. It is suitable for detecting and ranging targets at medium to close range, providing assistance in obstacle avoidance tasks. It can also complement RGB cameras.

- RGB camera: is the most commonly used sensor in perception systems, capable of extracting rich details and color information. However, its drawback lies in its limited ability to perceive distance and its susceptibility to lighting conditions. It is suitable for object detection and classification tasks.

Perception involves not only receiving sensory data but also processing this information through algorithms to help the robot comprehend the external environment and its current state. Current cutting-edge approaches primarily utilize deep learning to achieve environmental perception for robot systems. Some perception methods used in autonomous driving, such as object detection and tracking, and scene semantic segmentation, can also be applied to robotics.

For example, visual recognition and object detection can be accomplished in tracking tasks using methods like YOLO, followed by object tracking using techniques such as DeepSort. Moreover, researchers are exploring more intuitive and efficient end-to-end joint object detection and tracking approaches compared to traditional tracking-by-detection frameworks. Additionally, some existing approaches can facilitate obstacle avoidance and local path-planning tasks using cameras and lidar sensors.

Due to the capabilities of lidar, environmental reconstruction through mapping without using deep learning algorithms is possible, followed by obstacle avoidance through path planning algorithms. Furthermore, as robots can carry various sensors and powerful onboard processors, managing information from all sensors, such as fusing information from multiple sensors and multimodal perception, has also become a focal point in the robot industry.

Path planning

Navigation plays a key role in the functionality of mobile robots, a technology commonly utilized and developed for autonomous driving. Path planning involves the use of perception data by robots to calculate a feasible route to a specified destination. Generally, planning is categorized into global path planning and local path planning.

- Global path planning entails determining an optimal path within the entire environment through global mapping and GPS based on the map.

-

Search-based Path Planning Algorithm: A* combines the advantages of BFS (Breadth First Search) and Dijkstra’s algorithm, calculating the priority of each node during the search process. The priority calculation formula for a node is given by:

\[f(n)=g(n)+h(n)\]where:

- $f(n)$ represents the overall priority of node $n$. When selecting the next node to traverse, we always choose the node with the highest overall priority (i.e., the smallest value).

- $g(n)$ denotes the cost from the starting point to node $n$.

- $h(n)$ denotes the estimated cost from node $n$ to the endpoint, serving as the heuristic function of the A* algorithm. This heuristic function can be represented as the Euclidean distance: $\sqrt{(x_2-x_1)^2 + (y_2-y_1)^2}$, corresponding to the current node P1$(x_1, y_1)$ and the endpoint P2$(x_2,y_2)$.

During the computation process, the A* algorithm selects the node with the smallest $f(n)$ value (w/ highest priority) from the priority queue as the next node to be traversed.

-

Sampling-based Path Planning Algorithm:

RRT (Rapidly exploring Random Tree) is an efficient planning method in multi-dimensional space. It begins with an initial point as the root node and, through random sampling, expands the tree by adding leaf nodes. This process results in the creation of a random exploration tree. When the leaf nodes of this random tree include the target point or enter the target area, a path from the initial point to the target point can be found within the random tree.

-

- Local path planning does not demand comprehensive information about the entire environment. Its focus is on maneuvering the robot around obstacles in its immediate vicinity and adjusting the path based on real-time state information from sensors. Real-world applications of local path planning include tasks like tracking and obstacle avoidance.

- Real-Time Path Planning Algorithm: Compared to A*, D* is different in that its cost computation may change during the algorithm’s execution, primarily addressing path planning problems based on assumption. As the robot progresses along a path, it observes new map information (such as unknown obstacles), adding this information to its map and, if necessary, recalculating the new shortest path from its current position to the specified target. It repeats this process until reaching the target position or determining that reaching the target is not feasible.

- Reinforcement learning can be employed for both global and local path planning. Navigation strategies can be effectively trained based on constructed environment models, enabling robots to adapt to dynamic environments. Through the adjustment of training objectives and reward functions, robot agents can be trained to learn various planning tasks. However, as the path planning policy is trained through trial and error, real-world reinforcement learning also requires consideration of safety, efficiency, and generalization to diverse environments.

In addition to path planning algorithms, building maps through perceptual information is crucial. SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) technology accomplishes the self-localization of the robot and constructs environmental maps. Furthermore, using the fusion of various sensor information, it can accurately reconstruct the environment in three dimensions.

Control

In recent years, learning-based control systems have become more widely applicable to robots. Through the use of deep reinforcement learning, a robust robot control policy can be trained. In comparison to traditional control methods, the reinforcement learning approach is adaptable to various robots, substantially reducing the need for parameter tuning and achieving enhanced performance across different robotic platforms. Furthermore, learning-based control methods excel in integrating external perceptual information, such as visual data, by leveraging the strong representation power of neural networks to process multi-modal information effectively.

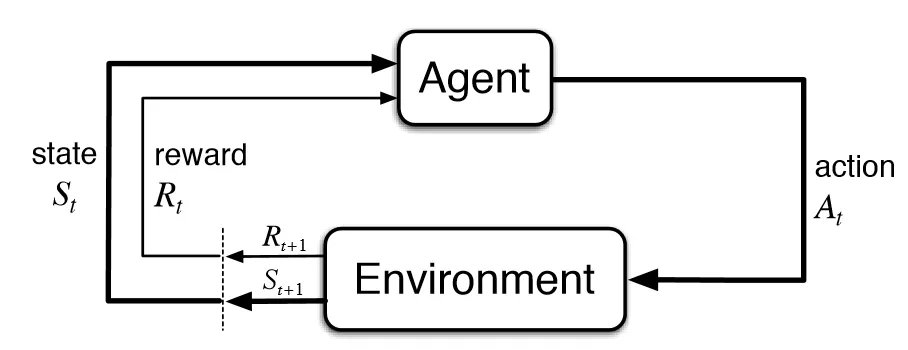

Reinforcement learning, a prominent machine learning technique, empowers agents to make optimal decisions by mimicking the human learning process, where experience is collected through trial and error to improve decision-making. As figure shows, within this learning framework, the reward and penalty mechanism ensures that the agent receives feedback after each action. This feedback enables the algorithm to train the agent to make optimal decisions in complex environments, aligning with long-term goals.

Deep reinforcement learning leverages the power of neural networks to handle high-dimensional input, thereby exhibiting robustness and generalization capabilities, even in highly complex environments.

Generally, contemporary reinforcement learning control methods are primarily trained on simulation platforms, offering a more generalized approach. However, there are also methods that train for specific robot scenarios by utilizing data collected from real-world experiences.

In the domain of learning-based robotics, simulators play a crucial role. These platforms involve the construction of scenes resembling real-world environments and the inclusion of robot models for training. Presently, prominent simulators for learning-based robotics include MuJoCo, PyBullet, and IsaacGym:

- MuJoCo: DeepMind Control Suite, developed by Google DeepMind, offers a software stack for physics-based simulation and Reinforcement Learning environments, utilizing the MuJoCo physics engine. MuJoCo is an open-source physics engine designed for robotics and biomechanics simulation, renowned for its speed and accuracy in simulating complex dynamic systems.

- PyBullet: open-sourced physics simulation for games, visual effects, robotics, and reinforcement learning. The community provides a rich set of tools for robot simulation, reinforcement learning, and motion planning, offering an accessible setup, particularly suitable for beginners.

-

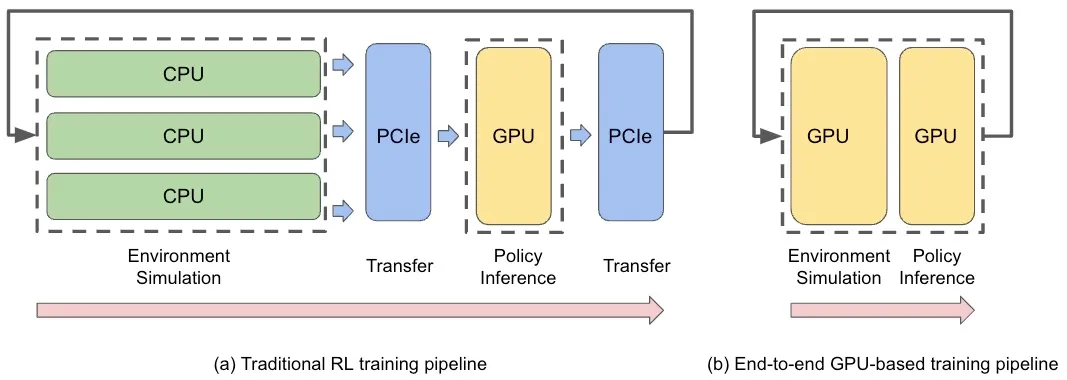

IsaacGym: NVIDIA’s physics simulation environment for reinforcement learning research, enabling reinforcement learning to leverage simulators for data collection and policy training. It is capable of conducting massively parallel simulations on NVIDIA’s GPU hardware, effectively reducing the amount of computations during simulation.

However, the simulator does not replicate the real-world environment, leading to a gap between simulation and reality, often referred to as the “sim-to-real gap.”

To solve this problem, researchers have proposed several methods that effectively reduce the sim-to-real gap.

-

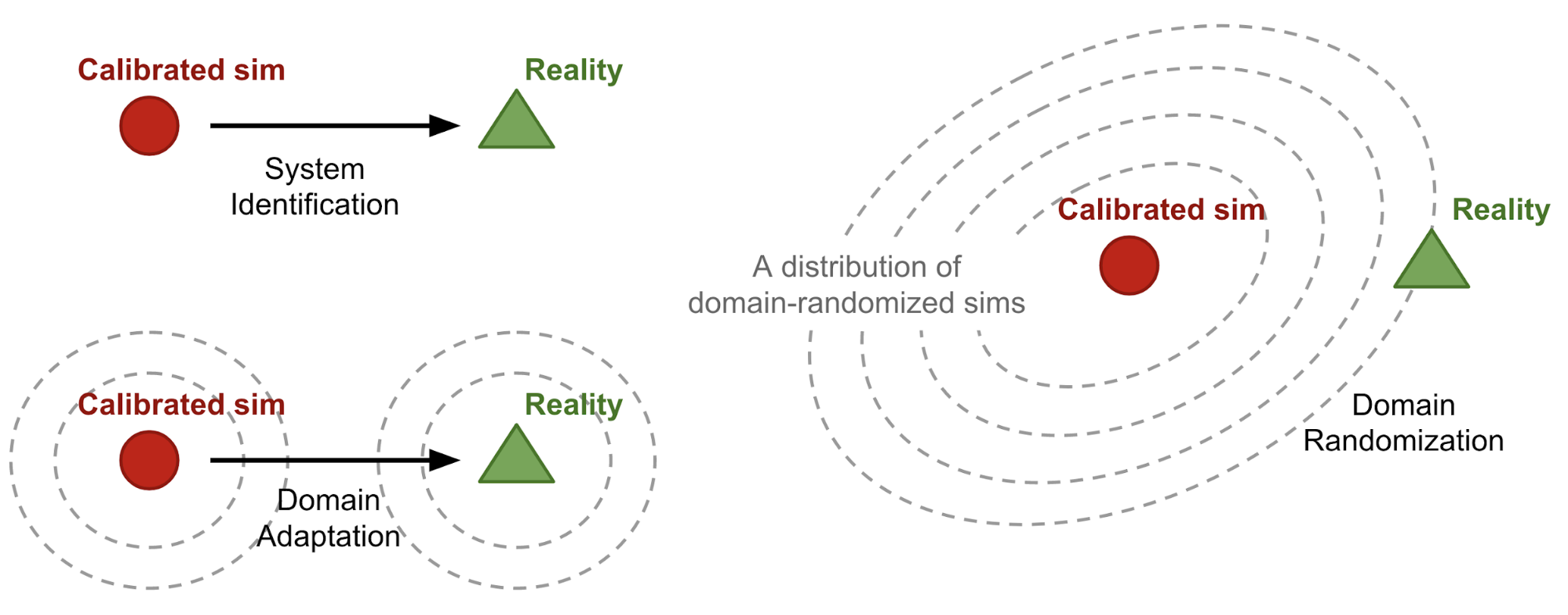

System Identification

Employing a more precise simulator to replicate real-world environments involves establishing an accurate mathematical model for a physical system. Thereby, the challenge of obtaining such realistic simulators remains. Current simulators struggle to generate high-quality renderings that mimic real vision, and they cannot perfectly emulate the intricate physical laws governing complex robot mechanics and environments. Consequently, the accuracy of these simulators is significantly compromised. Moreover, external disturbances in the real world constantly change the real-world environment. However, the simulation system effectively operates as a closed sandbox, where the next state is predictable.

-

Imitation Learning

Using expert demonstrations instead of manually constructing fixed reward functions for training models yields more similar locomotion control as we expected, enhancing the model’s adaptability during the transition to real-world environments. This approach, often referred to as behavioral cloning (BC) in imitation learning, leverages expert experiences. The student-teacher model is another imitation learning method and is a form of knowledge distillation. It can guide the training of a simplified student model through a more complex teacher model to achieve similar performance. Unlike behavioral cloning, the student-teacher model requires an expert model, while BC can rely solely on expert data. Nevertheless, these two methods share similarities, as the student-teacher model can exclusively use data collected from the interaction between the teacher model and the environment as expert data, effectively conducting online behavioral cloning. Additionally, Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) is a relatively new approach that incorporates Generative adversarial network (GAN) into Imitation Learning. Here, the Generator serves as a policy network generating action sequences, while the Discriminator determines whether these sequences resemble expert actions, providing output as a reward. When training high-performing and saltable policy models on robots through reinforcement learning, complex and highly parameterized reward functions are typically required. However, the GAIL method effectively mitigates this issue. Recent state-of-the-art solutions have successfully employed GAIL, demonstrating promising results.

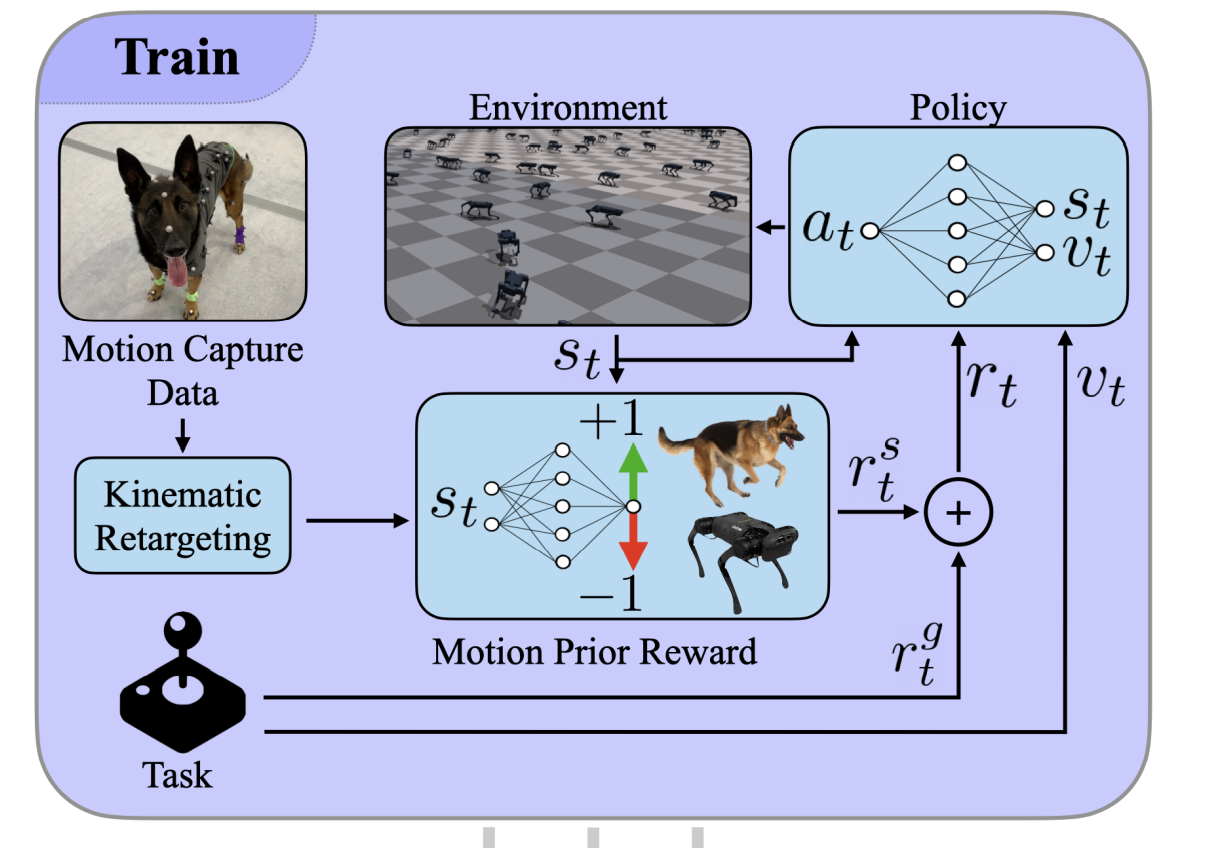

Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP) applies GAIL to legged robots, dividing rewards into two components. One focuses on Task Rewards, aiming to guide legged robots to move according to input commands. The other, Style Rewards, is to regulate the gait of legged robots during locomotion, making it closer to the expert provided by motion capture data from the movement of real dogs. After each action, the Discriminator of the GAN evaluates the style to produce specific reward values. Subsequently, the task and style rewards are integrated to update the policy network through reinforcement learning, which is the generator of the GAN.

-

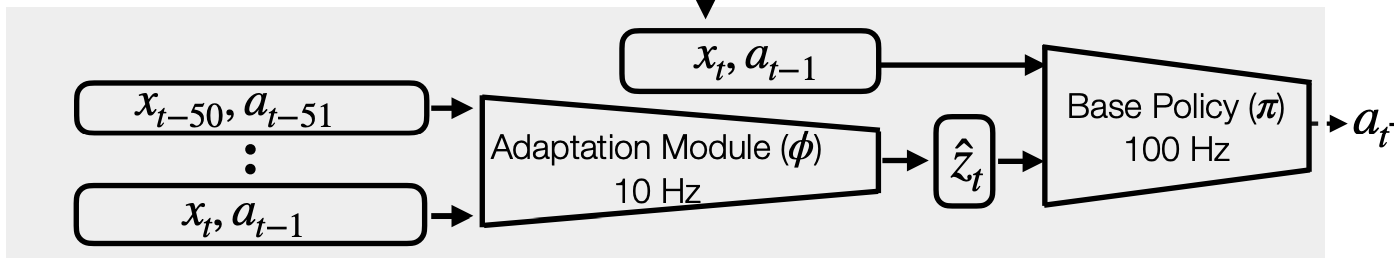

Domain Adaptation

Learning a mapping from the shared state space of both the simulated and real-world environments to a latent space. Subsequently, this mapped state space is used for policy training within the simulated environment. The model trained in the simulated environment using this mapping from the state space to the latent space can directly apply to the real-world environment without any fine-tuning. Basically, the implementation method involves training an adaptation module within the simulator, serving as the mapping from the state space to the latent space. This training process commonly employs supervised learning, allowing the adaptation module to learn implicit information from explicit states. Consequently, this information can assist the policy in making better decisions within the real-world environment. Typically, such adaptation modules can be constructed using temporal sequence models like RNN and Transformer to process a sequence of states over time, thereby predicting the latent states of the subsequent time step to help decision-making.

-

Domain Randomization

Introducing randomization of parameters in the simulated environment, including factors such as physical friction and visual object color, enables these randomized parameters to cover the range of corresponding parameters in the real environment. Generally, randomizing dynamic parameters can directly influence various aspects of the simulated robot, such as weight, friction coefficients, and IMU offsets. Furthermore, introducing random external disturbances, such as applying random external forces to the robot within the simulation environment, can enhance the resilience of trained policies when deployed in a real-world environment. However, these methods come with a trade-off: while they bolster robustness, they may limit the performance of the control policy at the same time.

Conceptual illustrations of three approaches for sim2real transfer. (Image source: Lilian Weng, 2019)

Future Trends

End-to-End Learning-Based Control

In recent years, using reinforcement learning in robot control has become common. Whether using model-based or model-free techniques, there are many successful cases using deep reinforcement learning in robot control. However, much of the work still focuses on specific modules within robot control. There remains significant difficulty in using RL to achieve End-to-End Learning of visual motion controllers for performing long-span, multi-stage control tasks.

The end-to-end robot control policy requires understanding the environmental state from noisy, multimodal, partially observed data obtained from sensors but also needs to achieve end-to-end policy behaviors such as navigation to joint control with limited information. It means that the robot can output specific control behaviors by inputting multimodal sensory information through the power of neural networks.

As a pioneer in AI-powered robots, Tesla’s humanoid robot Optimus also adopts end-to-end neural network control: taking video input, producing control output, and thereby controlling the motion of its components and joints.

LLM based control

As the most popular AI technology in recent days, researchers are currently enthusiastic about how to utilize LLM in robots. The capabilities of LLM are widely recognized. This model not only possesses general knowledge, enabling it to have a certain understanding of the entire world, but also exhibits strong generalization abilities, allowing it to process and generate corresponding responses to different sequential inputs. Building upon this, researchers have developed large-scale models with multimodal capabilities based on pure-text LLM. This multimodal LLM represents a significant advancement in data processing capabilities, as it can handle vision, text, audio, and even IMU data.

This research direction is also summarized by scholars as Embodied AI, which combines AI technologies such as NLP, CV, RL, and others in specific real-world applications. Interaction with the physical world has also become a key focus of Embodied AI, aiming to bridge the gap between digital AI and the real world. Robots are the most commonly used specific implementation platform in this direction. Through this, intelligent embodied AI agents can perceive and interact with the real environment, and then, like humans, achieve actions different from instructive behaviors through the LLM “brain”.

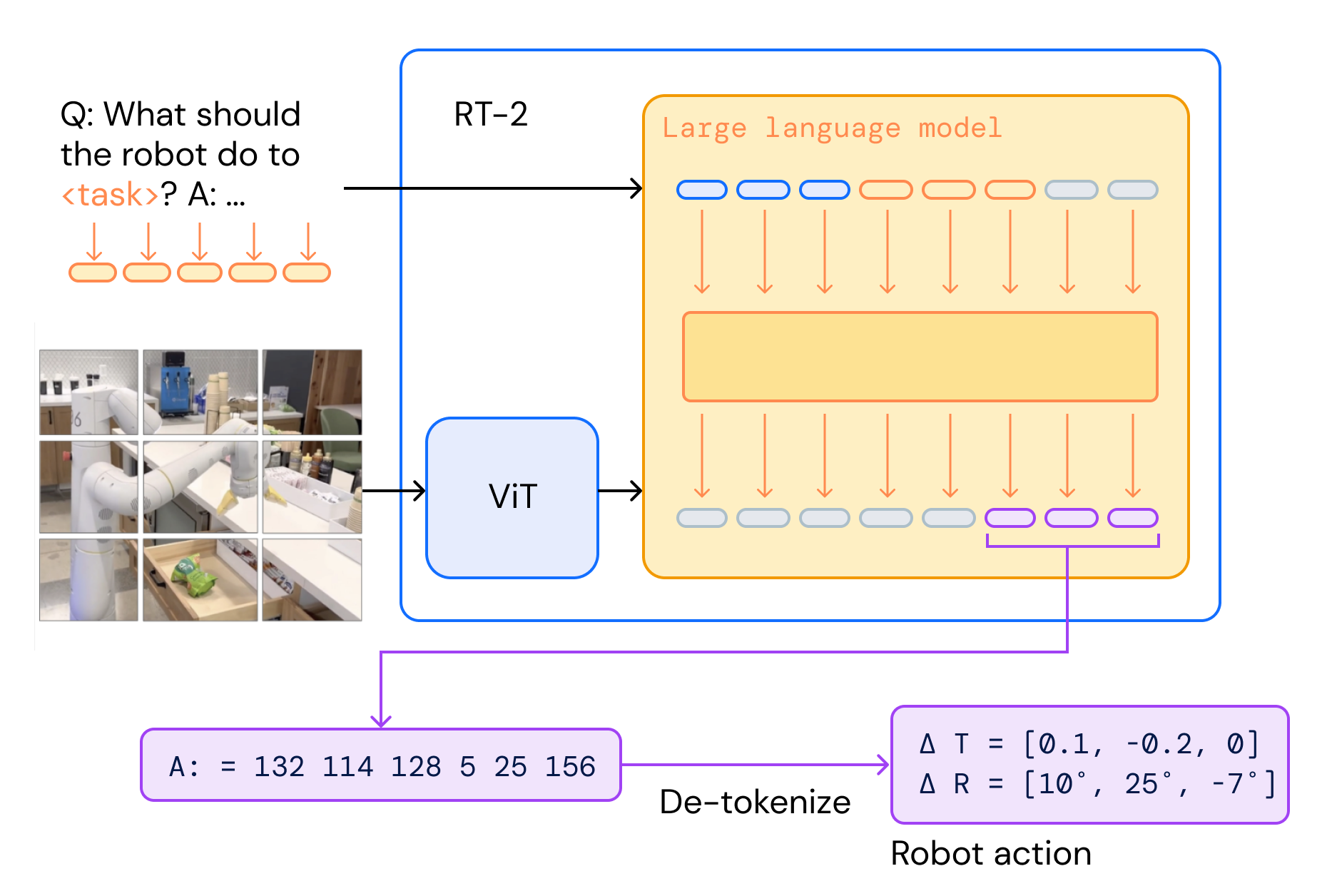

RT-2 combines multimodal LLM to achieve end-to-end control, as illustrated in the figure. Google uses the vision-language model PaLI-X as the baseline model, encoding the robot’s actions into text strings as language output. They fine-tune the model with these actions alongside Internet-scale vision-language datasets and then turn the vision-language model into a vision-language-action model.

In complex real-world environments, the model receives multimodal instructions and then outputs corresponding actions that can be executed in the real environment, thereby completing a series of tasks including navigation, manipulation, and instruction following. Current related work, such as Google Robotics’ Robot Transformer series, can convert prompts and visual perceptions into tokens that LLM can understand, and then directly output corresponding behavioral actions end-to-end.

In an era where AI applications are becoming increasingly prevalent, AI-powered robots can apply these AI applications in a more specific and intuitive manner in real life. Moreover, AI-powered robots are not like chatbots on the internet; they will become helpful assistants to people, and I believe they can change our lives in the future.

References

- Sutton, Richard S., and Andrew G. Barto. ”Reinforcement learning: An introduction”. MIT press (2018).

- YOLOv8: github

- Wojke, et al. “Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric.” ICIP (2017).

- Jonathan Ho and Stefano Ermon. “Generative adversarial imitation learning.” Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016).

- Todorov, et al. “MuJoCo: A physics engine for model-based control.” IROS

- Erwin Coumans and Yunfei Bai. “PyBullet, a Python module for physics simulation for games, robotics and machine learning.” (2016).

- Viktor Makoviychuk, et al. “Isaac Gym: High Performance GPU-Based Physics Simulation For Robot Learning.” arXiv preprint (2021).

- Anthony Brohan, et al. “RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control.” arXiv preprint (2023).

- Xi Chen, et al. “PaLI-X: On Scaling up a Multilingual Vision and Language Model” arXiv preprint (2023).

- Alejandro Escontrela, et al. “Adversarial Motion Priors Make Good Substitutes for Complex Reward Functions.” IROS (2022).

- Ian J. Goodfellow, et al. “Generative Adversarial Nets.” NIPS (2014).

- Ashish Kumar, et al. “RMA: Rapid Motor Adaptation for Legged Robots.” RSS (2021).

- Lilian Weng. “Domain Randomization for Sim2Real Transfer.” lilianweng.github.io (2019).